If we’re to believe the claims of a recently created website called “Denver Tech Future,” the fifth generation of the cellular wireless network is coming to us, and it will usher in a new era of digital interconnectedness that will be so transformational, it will constitute a – Fourth Industrial Revolution. 5G, as it is called, aims to eventually replace the existing 4G LTE network to provide much faster mobile data access.

And Denver is one of the first U.S. cities where Verizon and other telecommunications companies are at work installing backpack-sized super-powerful antennas with the goal of making 5G a reality and, purportedly, jumpstarting that Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Verizon, the $233 billion telecommunications company, created the Denver Tech Future website, which it calls a “community-focused initiative.” According to Denver Tech Future, 5G will lay the groundwork for the Internet of Things, in which the basic items of our daily existence — refrigerators, lamps, cars, etc. — will send data to each other automatically.

It will help make augmented reality, in which a computer-generated image is superimposed on our view of the real world, an essential feature of navigation. Once we’re able to share massive amounts of information at lightning speeds, Denver Tech Future’s website says, it will “change society in unpredictable ways” at an “exponential pace.”

But in the view of many Denver residents, 5G is nothing but an infrastructural nightmare — an eyesore and a burden on their property value — and a source of endless worry about potentially adverse health effects.

Although it’s only available in small areas of a few cities right now, 5G has already gotten a lot of hype and stirred an equal amount of controversy. The 5G network, carriers claim, would make cellular data connections 100 times faster than what we have today — so fast that you could download a two-hour movie in less than 3.4 seconds (it takes six minutes on 4G at best).

It would also improve “latency” for everything on the Internet, virtually eliminating that aggravating lag between when you click on a link and when you see the page load. If it all pans out, it could eliminate the need for any cable or wire to access the Internet at all, making wifi obsolete.

But there’s a catch. Actually, there are a lot of catches, including increasing the risk of cyberattacks and potential for surveillance, and exacerbating the divide in Internet access between rural and urban areas. But 5G operates on a much higher electromagnetic frequency spectrum than previous mobile networks.

The wavelengths it sends out have a higher capacity but a shorter range, which means that large towers that serve dozens of square miles won’t cut it. To make the network effective, “small cells” will have to be placed every few hundred feet.

And even then, it will be difficult for waves to penetrate through walls, trees, cars or glass, impeding indoor coverage. Not least, to access the network in the first place, you’ll need to buy a 5G-enabled smartphone and add 5G access to your plan.

According to Heather Burke, a spokeswoman for Denver Public Works, 122 new poles, each about thirty feet tall, have been constructed specifically to house this new small-cell technology. They’re labeled “CityPoles” by the Boulder-based company that builds the physical infrastructure.

Many are owned by Verizon, but some are also owned by AT&T, Crown Castle or Zayo Group (the latter two are companies that build small cells and lease them to carriers). This map shows where proposed and existing poles are.

Additional small cells have been installed in existing street lights and utility poles, all of which are owned by Xcel Energy. After Denver Public Works requested that companies integrate small cells into existing towers instead of building their own.

Xcel agreed to sell space on its monopoly of vertical infrastructure (for how much is unclear — Xcel and companies signed non-disclosure agreements). Verizon has also asked to put small cells on traffic lights (which Xcel also owns), but the city is still evaluating whether to allow that.

The purpose of the small cells is twofold. Some of the poles will house technology that aims to “densify” and improve the existing 4G LTE network, which is being strained as demand for wireless data increases. Others will lay the groundwork for the potentially much more powerful next-generation 5G service.

Because 5G small cells cover a much shorter distance, there will eventually have to be more of them — hence the demand for freestanding poles. Because each pole only houses technology for one mobile carrier, Denver could see hundreds or thousands more as companies expand their 5G networks in the coming years. As of now, there’s no way to know whether a pole houses a 5G cell, a 4G cell, or both.

According to Verizon spokeswoman Heidi Flato, Denver’s 5G network will first be concentrated in Highland, LoDo, Capitol Hill, Denver Tech Center, and around popular landmarks. Verizon turned on its network in Denver July 1, Flato says.

All four major mobile carriers are working on implementing 5G networks, but as Verizon puts it, “There is 5G, and then there is Verizon 5G Ultra Wideband.” AT&T has yet to launch 5G for consumers, T-Mobile’s network is in a limited startup phase, and Sprint (which is set to merge with T-Mobile pending a Federal Communications Commission vote) has a network.

But testers found it was on average more than three times slower than Verizon’s. Verizon is right: It’s the leader in this technology so far, at least in Denver. But that’s also making it the face of public discontent.

The Federal Communications Commission has done its best to make it easy for companies to implement small-cell infrastructure, putting caps on fees that municipalities can charge and requiring permits to be approved within ninety days. In 2017, Colorado passed a law that confirmed that telecommunications companies have the right to construct small cells in what’s called the “public right of way.”

In Denver, that’s the several-foot span that stretches inward from the street curb, and it’s owned or controlled by the city, even if it’s in someone’s yard. Companies must go through a permitting process with the Department of Public Works, which, according to Burke, regulates locations to ensure that poles are “less intrusive to the public and adjacent property owner.”

But, she wrote in an email to Westword, “Denver can’t limit how many there are or restrict access” because the law establishes that cities cannot flatly deny permits or favor one company over another; they can only regulate based on the protection of public health, safety and welfare.

Some residents are arguing the city should do just that, though. They take issue with what they see as the towers’ clunky, industrial appearance or fear that towers will reduce the property value of their house or turn customers away from their business. They point to San Francisco, where a court has allowed the city to limit 5G infrastructure for aesthetic reasons.

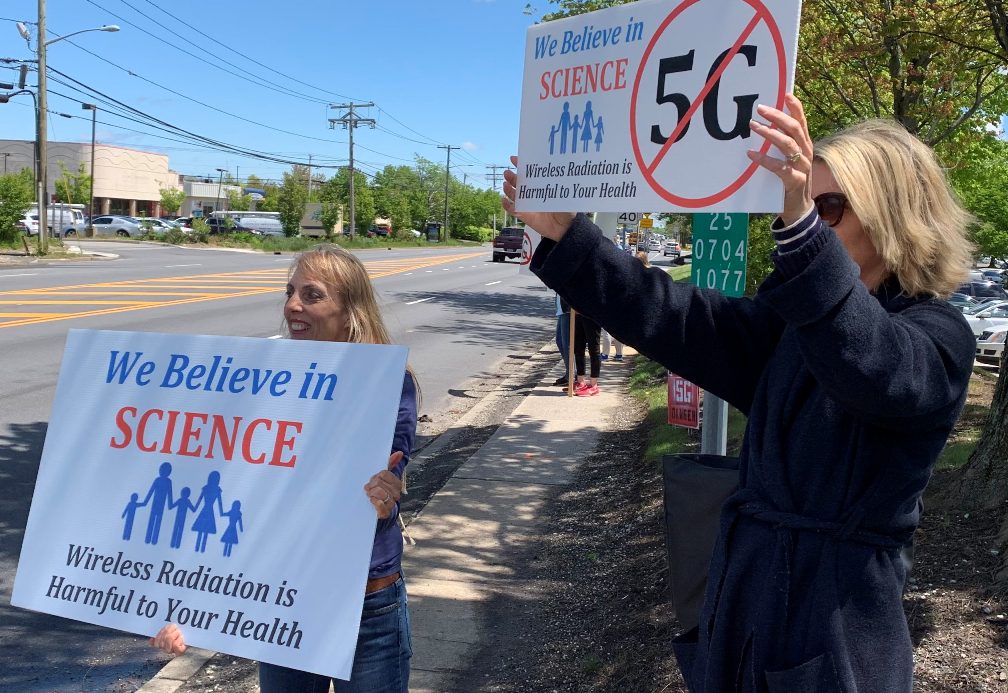

Others fear that they will get “microwaved”; that is, that the higher-frequency wavelengths will damage DNA, cells and organ systems, or even cause cancer. Brussels banned 5G because of health concerns in April, as have several small municipalities in California. Boulder held an educational panel on the health effects last month after residents and city councilwoman Cindy Carlisle raised claims against 5G.

Much of the frenzy surrounding the impacts of 5G radiation can be traced to a controversial 2000 study that raised alarms about wireless networks in schools after a researcher found that microwave absorption in brain tissue increases exponentially at frequencies above 1000 megahertz.

Scientists now say that study ignored the barrier effect of human skin. 5G networks, being complex new technology, will use many parts of the radio spectrum, which ranges from 3 kilohertz to 300 gigahertz; Verizon’s Ultra Wideband uses super-short “microwaves” ranging from 28 to 39 gigahertz.

The exposure levels for 5G networks fall well within the federal standard for safety for signals operating at that frequency. But many insist that those exposure levels haven’t been conclusively studied; a group of 180 scientists and doctors have petitioned the European Union to halt the 5G rollout. Continue reading