An undersea cable will emerge later this year near a popular sunbathing spot in the French port of Marseille.

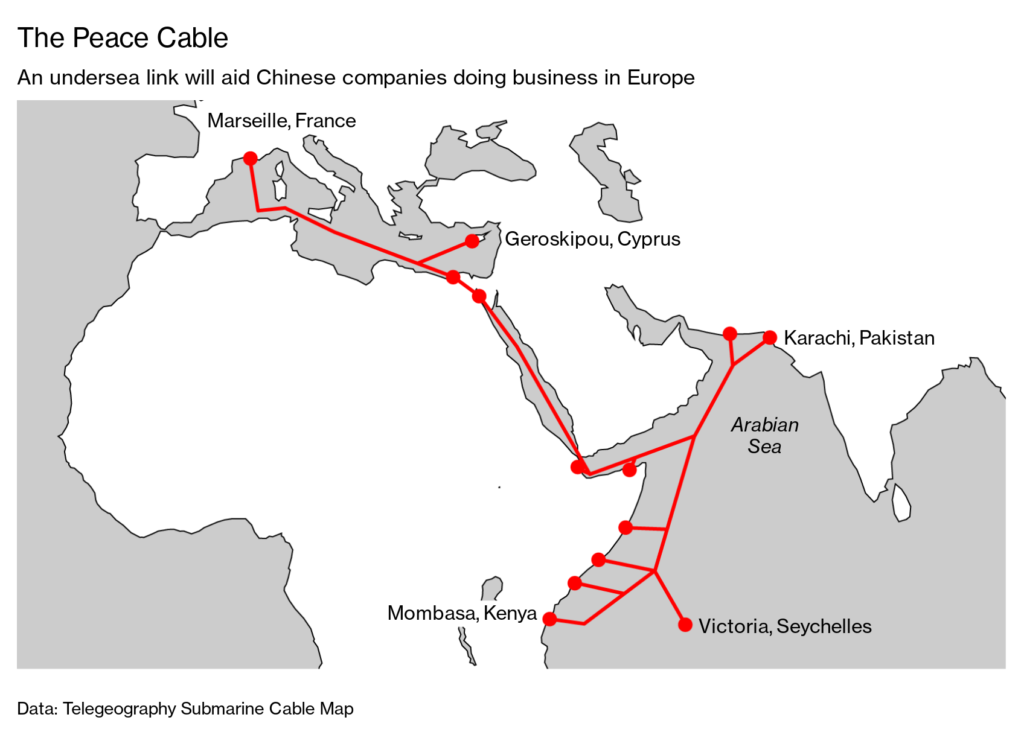

The cable, known as Peace, will travel over land from China to Pakistan, where it heads underwater and snakes along for about 7,500 miles of ocean floor via the Horn of Africa before terminating in France.

The Peace cable, which is being built by Chinese companies, will be able to transport enough data in one second for 90,000 hours of Netflix, and will largely serve to make service faster for Chinese companies doing business in Europe and Africa.

“This is a plan to project power beyond China toward Europe and Africa,” says Jean-Luc Vuillemin, the head of international networks at Orange SA, the French phone company that will operate the cable’s landing station in Marseille.

The project also represents a new flashpoint in the geopolitics of the internet.

Huawei Technologies Co., the company at the center of a long-simmering struggle between China and the U.S., is the third-largest shareholder in Hengtong Optic-Electric Co.—the company building the cable.

Huawei is also making the equipment for the Peace cable landing stations and its underwater transmission gear.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook Inc. say they won’t be using Peace because they have enough capacity already.

Even if they wanted to, using Peace would be hard for these companies to do, because of the U.S.-led boycott of many Chinese telecommunications equipment makers, including Huawei, for national security reasons.

RELATED: Facebook Submarine Cable Contractor In Trouble

Undersea cables have significant strategic importance. Right now, some 400 of them carry about 98% of international internet data and telephone traffic around the world.

Many of them are owned and operated by U.S. companies—helping reinforce U.S. dominance over the internet while giving a sense of security to the U.S. and its allies that may be concerned about sabotage or surveillance.

The U.S. has talked up the threat from Chinese-built infrastructure.

Last year, then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged the international community to “ensure the undersea cables connecting our country to the global internet are not subverted for intelligence gathering by the People’s Republic of China at hyper scale.”

The French government is prepared to stand up to additional pressure from the U.S. over the Peace cable, say people familiar with its thinking, who asked not to be named discussing national security matters.

It could look to mollify the U.S. by keeping certain types of traffic off the cable, said another person.

The government of French President Emmanuel Macron doesn’t want to isolate China from internet infrastructure, in part so France won’t have to “fully depend on U.S. decisions,” he said in an interview at the Atlantic Council in February.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel also objected to efforts to isolate China in a Feb. 5 press conference with Macron, saying she did not think decoupling from China was “the right way to go, especially in this digital age.”

Landing stations, such as the one near the beach in Marseille, are seen as the easiest spot for cable-tapping and are carefully secured.

There’s a risk during construction, when backdoors might be inserted to siphon information, according to security experts.

“Any time that you have your data traveling over their switches, their cables—these are the source of redirecting traffic and eavesdropping,” says Robert Spalding, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute policy group in Washington. “It’s just common sense.”

Limiting use of internet infrastructure for security reasons has its costs. Mike Hollands, a sales executive at data center company Interxion, which is involved in the Peace project, says restricting the number of users connected to a data network will slow down overall connectivity.

“The performance of the internet is optimized when traffic can flow via all available cables in an unrestricted way,” Hollands says.

The global submarine cable system may become only more fragmented.

The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies and the Netherlands-based Leiden Asia Center estimates that by 2019, China had become a landing point, owner, or supplier for 11.4% of the world’s undersea cables. It expects this proportion to grow to 20% between 2025 and 2030.

At certain points, the U.S. and its allies have blocked China’s path. In 2018, Australia scuppered a Huawei Marine Networks cable that would have connected the Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, and Sydney via a group of Pacific island nations.

Last year, a portion of an 8,000-mile cable from Los Angeles to Hong Kong, partly funded by Google and Facebook, was rerouted after U.S. national security officials blocked plans for a connection to territory that’s under Chinese control.

“It’s really a matter of regret to see those geopolitics descending right down the stack into the physical layers of the internet,” says Emily Taylor, a cyber policy expert and a fellow in security at the international affairs think tank Chatham House.

“What we’re all going to have to come to terms with this is: How do we try to keep as many doors open as we can without laying ourselves open to national security threats?” —With Thomas Seal